The eight remaining Sámi languages are spoken here in the north of Europe (see map and gallery below) in a cross-border region which includes Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Kola Peninsula of Russia. This region is generally called Sápmi – mostly by northern Sámis, and is sometimes referred to as Lapland or Samiland. Laponia in Swedish Lapland is the one of the World’s largest unmodified UNESCO nature area still cultured by natives. Sámis are indigenous to Sápmi/Northern Europe and Kola Peninsula, our heritage and ancestry traces back to Ural mountains and Siberia. Sámi is part of the Uralic language family, alongside Khanty, Mansi, Nganasan and Karelian, to mention a few. Lap is considered a deragatory term for Sámi person.

Sámi languages speakers estimate:

Southern Sámi 300 – 500 speakers

Ume Sámi – less than 20 speakers

Lule Sámi 2 000 – 3 000 speakers

Pite Sámi – less than 20 speakers

Northern Sámi – 20-30 000 speakers. There are three main North Sámi dialects.

Northern Sámi is the most accessible language, both in terms of literature, news broadcasts, and other material for those who want to learn a Sámi language as a foreign language.

Kemi Sámi – extinct

Inari Sámi 300 – 500 speakers

Akkala Sámi – considered mostly extinct since 2003

Kildin Sámi 300 – 700 speakers

Skolt Sámi 300 – 500 speakers in Finland, fewer than 20 speakers in Russia

Ter Sámi – less than 5 speakers left, all elderly (update 2023: Ter Sámi is extinct)

Today we are around 90 000 Sámis, but as you can see from the numbers they do not match up to speakers of Sámi languages. Roughly 4/10 Sámis speak and use one of the Sámi languages today.

Why is this so?

To avoid humiliation and to give their children “better chances in life”, indigenous and minority parents often decide to speak a dominant or official language with their children. Sámi parents have not been an exception to this rule, especially in the very near past.

For the sake of how long this post would be in order to include all four countries’ history with the Sámi people, I will mainly focus on Norway.

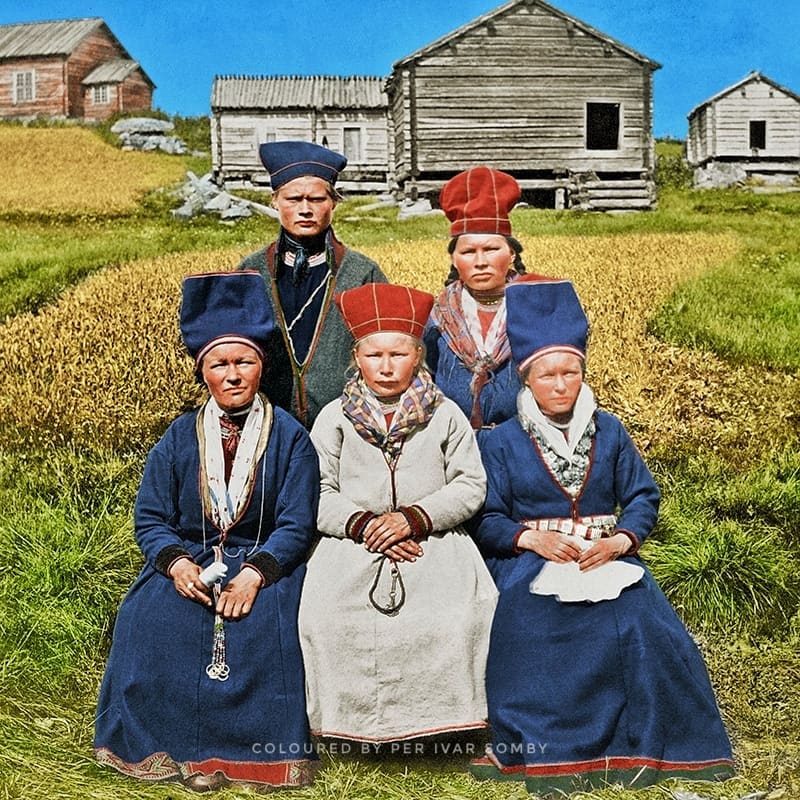

Opphaver: Fotograf Sverre A. Børretzen

Rettighetshaver: Leverandør NTB scanpix

Up to the 17th century, Sámi society lived pretty much its own life, with little interference from the outside. But with the new borders of the Nordic countries, interference was inevitable. Historically, the language situation after interference can be divided into three distinct periods: a missionary phase; a harsh assimilation phase; and the present phase, with potential for integration and revitalisation.

The 17th and 18th centuries characterise the beginning of missionary activities, with some very positive projects for the benefit of the Sámi languages: teaching was conducted through the medium of Sámi and religious texts were translated into Sámi (the Læstadian faith was introduced to Sápmi). From the middle of the 19th century however, a new policy based on national romanticism and ‘vulgar Darwinist ideas’ led to a harsh suppression of Sámi and the languages. The Norwegian Parliament and government pursued overtly a policy aiming at assimilating the whole Sámi population in Norway in the course of one generation. One can only say that this assimilation was very effective.

The “dark century,” 1870 to 1970 ca, had detrimental effects which can still be felt on both the languages themselves and on their status and speakers. In the coastal areas of Norway (and elsewhere), negative attitudes were transmitted by the Sámi themselves as a result of the policies, and inter-generational transfer of the language ceased in only a few generations.

New efforts in maintaining the languages were revived in the 1970s and still continues to this day. However, one of the most striking failures of the Sámi strategies is that the smaller Sámi languages (in numbers of speakers as listed above) have not seen success in improving their situation or even in defending their previous position. This failure is partly due to the fact that most speakers live apart from the larger Sámi groups. Dispersed among Norwegians, Swedes, Finns, and Russians, they do not have the demographic concentration that would enable them to use their language in the workplace and in official situations, including schools.

A language’s development, aging, and dying was considered “natural,” out of human reach. Languages were not killed, they “died of old age.” This agentless “model” for the prediction of the future of languages is still found among politicians, and legitimates their way of treating minority languages. The view that a minority is not autonomous and their own people, is devastating to that people’s culture and language.

In Norway, many municipalities with a Sámi population had developed procedures to give the Sámi some local linguistic rights. Yet, when the Sámi language law (in force since 1992) designated certain areas as belonging to the Sámi administrative districts, many of the municipalities left outside these official districts – often municipalities where the speakers of the smaller Sámi languages lived – withdrew services in Sámi, claiming that the law did not require them. Even today, there is strong resilience towards using official Sámi names in for example Norwegian towns and municipalities. This seems to stem from the view that Sámi people somehow belong to Norway, Sweden, Finland or other countries, and not to ourselves as our own people with our own unique language, history and culture.

Currently, education, official documents and the media use Northern Sámi almost exclusively. This variant is used as a de facto “official language” and the most significant efforts have gone into the development of this particular language, to the detriment of other Sámi languages.

Opinions also differ on whether the different versions of Sámi are actual languages or dialects, and how to designate their speakers. Here is a an example what ‘Have a good weekend’ is in 6 Sámi languages:

“Buorre vahkkoloahppa” – North Sami

“Buerie hïelje” – South Sami

«Buorre vahkkogiehtje» – Pite Sami

“Buorre vahkoloahppa” – Lule Sami

“Šiõǥǥ neä’ttel-loopp” – Skolt/East Sami

“Pyeri oholoppâ” – Inare Sami

Eastern Sámi is the most different from the other languages.

Most Sámis today speak either Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, Russian, or even English as their everyday tongue (some migrated to the USA). Many are bilingual as well. Another factor is that some Sámis do not identify as Sámi or even know that they are due to the heavy assimilation of the past. They do not have any relationship with the language(s), and thus have lost their door to that culture.

Norway, Sweden and Finland was in 2019 urged by the UN to increase public funding of Sámi parliaments as a response to the dire state of the disappearing languages. But even if the situation seems dire for many languages, it is still possible to revitalise them and start using them more often. Which languages survive and which do not ultimately seems to be a question of human will, not of any rules of nature.

I know that languages and cultures come and go, but I do feel it a great loss to lose what has been native for Sápmi for literally thousands of years, in only a few generations, when it can be perserved. I am happy that some schools and institutions are giving sámi language courses to anyone who wishes to learn it (although this is mostly in Northern sámi), and I do also wish that my children will learn it, which I never did due to the Norwegianization process in Finnmark. Language is a huge part of culture and when it’s taken away, people get confused about their own community, identify and sense of belonging, and even turn on each other as a result of feeling alienated.

The languages we learn from our parents shape our brains, literally!, and our worldview, how and who we relate to. The immense loss of language and culture for the Sámi people cannot be described as anything else but traumatic.

Thanks for reading! xx

Sources and texts used in this post:

https://site.uit.no/sagastallamin/

http://www.sorosoro.org/en/sami-languages/#:~:text=Yes.,beginning%20of%20the%2021st%20century.

https://blogs.loc.gov/international-collections/2019/12/will-the-sami-languages-disappear/

https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/saami-languages-present-and-future